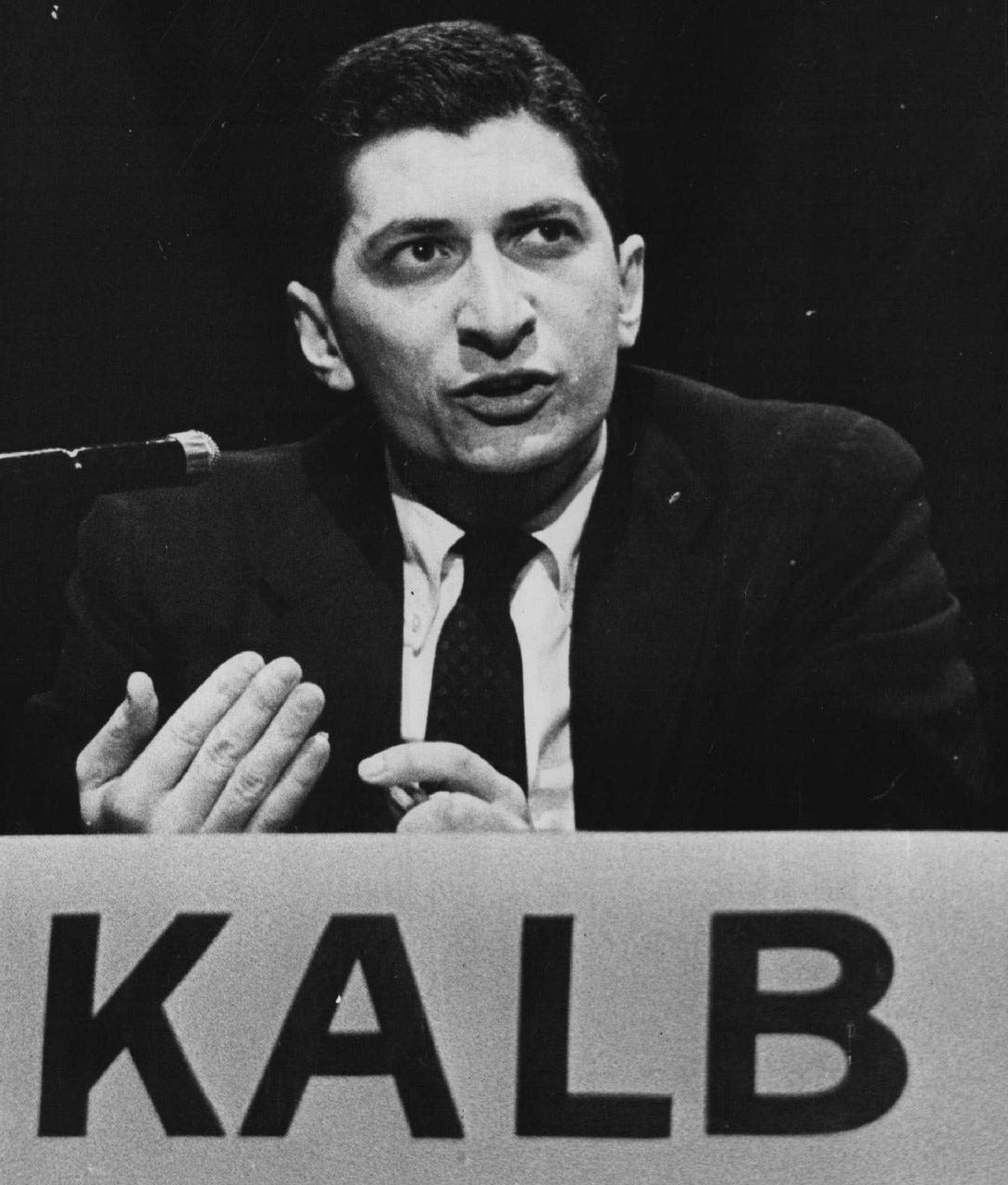

A conversation with Marvin Kalb about his book 'Assignment Russia: Becoming a Foreign Correspondent in the Crucible of the Cold War'

Working as a reporter, life in early 1960's Moscow, and being 'red or dead?'

American journalist Marvin Kalb looks back on the exciting start to his career in the midst of the Cold War. In the resulting memoir, Kalb recalls his early years as a journalist and the lead up to his role as CBS’s foreign correspondent in Moscow.

Assignment Russia begins in 1957 with a call from Edward R. Murrow, who invites Kalb to come work at CBS. He does not hesitate - he drops all work on his PhD and joins the famous band of “Murrow boys”. It then covers his early days at CBS writing early morning broadcasts, his round-the-world trip researching the state of the Sino-Soviet alliance, and a 1960 Paris pre-summit interview with Nikita Khrushchev discussing the Soviet response to the famous U2 plane crash. Finally, there is Moscow; Kalb navigates censorship, Russian bureaucracy at the Metropol hotel, and working as CBS’s Moscow correspondent.

“I vowed to myself that no matter the story or challenge, I would always conduct myself as if Murrow were still at CBS, a towering reminder that a reporter’s job was not to make news but to cover it—with honesty and humility, with fairness and dignity.” - Marvin Kalb, ‘Assignment Russia’

Your book, Assignment Russia, was about realizing your goal of becoming CBS’s Moscow correspondent. The journey itself was so interesting - the early days at CBS, your round-the-world trip in search of information on the state of the Sino-Soviet alliance, etc. After all, journalism is an incredibly dynamic field - as the world changes, the job changes. How did having this goal guide you throughout your career?

One of the things to bear in mind is that the time that I was working in is radically different from the time that you are going to start working as a reporter. I started in the midst of the Cold War. It was a very dangerous time. We in the United States were not absolutely certain about what the Soviet Union was going to do. They were by all indicators aggressive. They were seeking to take over - and did take over - large chunks of Eastern Europe. During the czarist times they had moved in and taken over Central Asia and Siberia, so there was an expansive current working within Russian history.

I happened to have developed an interest in Russia principally, I think, starting with an appreciation of Russian literature and of Russian intellectual history, especially in the 19th century, and the linking of the literature to the country’s politics, leading then to the revolution early in the 20th century. It was very exciting intellectual stuff. Whilst going from college to graduate school, I wasn't sure whether I wanted to be a teacher, journalist, or diplomat. I was a confused young man. But the one steady goal was somehow to link myself to a study of the Soviet Union. I was working at the US embassy for thirteen months in 1956 and ‘57. My Russian language - the use of the language - began to come quite easily to me at that time. I was able - through luck - to meet Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union. He took a liking to me I think, principally, because I'm so tall and he was so short. He kind of looked up at me all the time and he got a kick out of that. He referred to me as Peter the Great because Peter the Great was 6'7 and I was 6'3. So this was all luck. It wasn’t that I plotted any of this, I hadn’t. One thing just sort of led to another. Most importantly, because it was all taking place during the Cold War, the need for people to know about Russia was large, and in some branches almost desperate.

I wrote an article for The New York Times about Russian youth and Edward Murrow happened to read it. Did he have to read it? No, he just happened to and asked me to come down to meet with him, which I did. The secretary said it would be 30 minutes, I said fine, but he talked to me for three hours - from nine to noon. It wasn't my doing. He was the one who asked the questions and I just answered. And he was, to an extent I suppose, pleased and impressed and when the session was over he put his arm around me and said, “How would you like to join CBS?”. It was that simple. I had always wanted to be the CBS correspondent in Moscow, but getting there was not a plot on my part. The only part that was a plot would have been that I studied Russian history, I knew the language, I knew the literature. So I was ripe picking for a network that wanted to send somebody to Russia who at least knew something about the place.

That takes me to something I wanted to say to you. One of the most important things when you're looking for a job as a foreign correspondent is to have something in you that the network or the newspaper or the magazine is looking for or needs. Having a special skill is valuable. If you know all about oil, then it would make sense for somebody to hire you for a Middle East job. If you know something about German literature, well, that might mean something in Germany. In other words, you should know what you have to offer a network aside from the fact that you're well educated and you have a desire to be a reporter. That's great and essential, but what else do you have that might appeal to them? Keep that in the back of your mind.

You have mentioned that your mother was born in Kiev, Ukraine and your father came from Poland. Is your heritage what drew you to the study of the Soviet Union, or was it something else?

That's a very good question. The answer though is that my mother’s birthplace in Kiev and my father’s birthplace in a very small town west of Warsaw was totally irrelevant to the fact that I ended up in this field because - you may find this to be true in a number of different cases too - some people who leave an area really leave because they don’t want to have anything to do with it. In my mother’s case, the presence of a deep antisemitism in Kiev almost obliged her father and mother to seek a way out. They fled from Kiev and wanted nothing to do with it. It was the same for my father. When he was born in this very small town, it was part of the Russian empire. He was faced with antisemitism, the lack of economic opportunity, and political oppression. He wanted to get out of there. They both fled and ended up in the US and that's where they got married. However, their backgrounds had nothing to do with my attachment.

It started with a professor at The City College of New York named Hans Kohn. He was born in Prague and was a great expert of Russian intellectual history. I took a course with him when I was a junior in college and it overwhelmed me in the sense that his knowledge of the subject was so vast. He was such a good teacher. He inspired me to begin to study, read, and appreciate Russian writers and that was my route into Russia. It had nothing to do with my parents.

The Khrushchev pre-summit interview and the Pasternak funeral footage loss that you write about in the book seem connected in the sense that Khrushchev going on his morning walk and the woman transporting the footage are both individuals whose actions are depended upon in the making of a news story. One event was successful, the other was not. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the fragility of information and the reliance on other people that journalism entails.

A journalist is as good as the information he or she has. That means that the acquisition of information is central to the work of a journalist. A journalist has to have a good set of eyes and ears, an appreciation of people's sensitivities and background, and an ability to sort of spot a potential source. Not owing it in advance, and not really stumbling upon it, although that sometimes happens. What is important is your judgement of a person - whether that person is worth talking to and how, if you begin a conversation, do you proceed? Do you try to impress them that you're a great journalist? ‘I'm giving you the honor of meeting me?’ - no, no, no. What is it that you could impress upon them that would make them feel that they are contributing to something? In other words, they are contributing to your ability to tell a story about Russia to the American people. Let's say you bumped into an American by chance who happens to have heard you on radio or seen you on television. That is a phenomenal advantage for a radio-television reporter because people are always impressed. ‘Oh, could I have seen that guy on television?’. That is a big asset, but you don't overplay it. If you overplay it, people will think you're just a guy trying to play the role of a bigshot. No, no, no. You have to be yourself. I have always found that the best way of getting through to somebody is to be authentic. Don’t lie, be yourself. Tell them what it is that you need and why you need it because, after all, what is it that you're selling? You're not a spy, you're not a businessman, and beyond your salary you’re not making any money. In those days the salary wasn't all that great anyway. The only thing you could use to sell somebody on helping you is that the person has to be persuaded that what he or she is doing is in the interest of informing the American people on what it is that's happening.

If, for example, you have this story of Pasternak's death and you have the footage of a phenomenal funeral service but, damnit, how do you get it out of the country? So you've got to go to the airport and spot somebody. Now, in Moscow in those days at the airport and maybe even today by the way, people looked rather frightened and a little cautious about talking to somebody else - they just wanted to get out - so it wasn't easy to spot somebody, but in this particular case with that footage this woman seemed to me to look like a thousand other women I've seen in New York. And it turns out she was from New York. And her daughter had seen me on television and she was very ooh aah about that whole thing. So I had an in. The question was, how do I persuade the mother to do something that is, to an extent, dangerous? I didn't lie. I told her, “It's not allowed to take footage out of the country that has not been exposed. You've got to do that. But this is what the footage is, help me out”. So she did, but the footage, as you know from reading the book, never got to where it should've gotten.

These situations really seem to represent the highs and lows of the job.

Very much so, it is a high and low. But for the most part it's a high, because it's a wonderful way of earning a living and it is valuable. We are still in this country a democracy. We still rely on a free exchange of information. A journalist is an essential part of the process of democracy. I'm not inflating the role of a journalist, that's just a fact. Also, as a fact, if you can fit into that role and enjoy it, then you've got it made. I mean, it's a wonderful experience and I know quite a few young ladies who have gone into journalism a little concerned, thinking, ‘Will I make it?’, and they've been terrific, they really have. I think that we have arrived at a time now when you can sort of, if that is a concern of yours, I think that for the most part you can drop that. It's not going to stop you anymore. I think if you're good it doesn't matter. Being male or female, or your age. I always found that the young journalist who is well educated is almost to be preferred over an old-timer because the young journalist still has fire within her, still is determined, eager to do it. You know, you get to be an old man and you sort of sit back. I fortunately retained my eagerness but most people I know my age have moved on.

What is your relationship to Moscow as a place where you lived and spent a significant part of your life? How do you feel about it outside of your work?

Moscow's a fascinating city. A fascinating city with a fascinating history, and because I had studied the history before I set eyes on Moscow, I had my own internal vision of what I was going to find, and I was not disappointed. The preparation for Moscow was real, it was extensive, it was deep, and when I got there I looked at it and I recognized it. I wasn't bowled over by anything I saw. I knew it because I had read so much about it so it didn't shock me, surprise me in any way, but it reinforced my earlier positive impression of it. There are parts of Moscow which are quite stunning, beautiful, and there are many parts which are hideous. The political system gives it a special kind of reality. In other words, if you are in the time of this book, in the early 1960’s, Russia was very much a dictatorship, but it was a dictatorship with the beginning of a reformist tendency with Nikita Khrushchev. However, when he tried to move too far, the conservatives got him. They kicked him out of power in ‘64. That was the end of the reform effort. You had to wait then, until Gorbachev 30 years later, before you had another reformist effort. And that was killed by Putin. So Russia goes sort of up and down politically.

As far as the Russian people are concerned, they were absolutely consistent with the literature. If you read Tolstoy, Chekhov, Pushkin, if you read those three, you then have a pretty good sense of what the Russian people are like. They are very interesting. At the very beginning they want nothing to do with you, but very quickly if you can somehow get through - and the knowledge of the language is essential at this point - like if you're on a train, a little booth on a train for example, and there's room for four people, two and two, and you're sitting there and they are all Russian and you don't know the language, what do you expect them to do? Unless they know English, there's nothing for you to say. However, if you know Russian and in a nice way begin a conversation, not intrusively, not seeking something very private - just, you know, ‘how's the day, what's it like, oh what are you eating there’ or something - you will find them to be very quickly your best friend. And that's so wonderful. That was terrific, I enjoyed that.

Have you read Turgenev's Fathers and Sons? The novel explores the concept of generations - which I think is crucial to the conversation about the attitudes of Russian citizens - and is still relevant today even though the book was written in the 19th century.

Yes I have. And the time period really doesn't make any difference. It really doesn't make any difference. A sound Russian book. Turgenev especially has an ability to speak to all ages because his people are so real, you can place them anywhere. You can recognize them because they are so real. He is a great writer.

Do you believe that a country and its people can ever truly be considered as separate from its politics?

I understand where you’re going and that's a very good question. I have a feeling that, with different people, the response is different. In Russia, the people today are familiar with an authoritarian, even dictatorial system of government. They are familiar with it from stories their parents and grandparents told them, and from the literature that they've read. They know it from their own life experience. Russians - and here I may be wrong, completely wrong - I do not believe are overly distressed with living in an authoritarian form of government because they are, in a sense, used to that form of government. If they are denied individual liberty they shrug and say, you know, ‘My father had that same experience. He also could not do this and that’. Whereas, if you did that to a Frenchman he might go into instant rebellion. Or a Canadian, because of their backgrounds. The answer to your question is yes, there is a direct relationship between a people and the political system of government in which they live. What their aspirations are; There are many Russians today who aspire to freedom, to individual liberty, but they are unable to express themselves in the current political environment and they continue to live there. Some of them leave, but most of them stick around and say to themselves that, ‘Well, my dad lived through this - I can too’.

Do you feel that the time you spent living in Moscow influenced you as a person and, if so, how?

I'll tell you this - the book I'm currently writing goes on into 1961 and ‘62. I'm currently writing a part that takes place in 1961. At the end of ‘61, CBS had a program called Years of Crisis where they brought all of the foreign correspondents back and we had a discussion. The executive producer of the program staged a question that was asked of me, but I did not know it was staged. And the question at the time was, ‘Would you rather be red or dead?’. That was a phrase that was used in 1961 in America, and it was a hot phrase. People used it all the time - ‘Rather red or dead?’. When I was asked that question - and I'm trying to write that section now so I went back and looked at the broadcast - I could see on my face that I was surprised by the question and I had to give it a moment of thought. My answer was that I know a lot of people in the Soviet Union and they are neither red nor dead. I thought that was a good answer and it sort of shut him up - the guy who asked me this question. Then he came back and said, ‘No, no, no, what about you?’. To answer your question, I could tell you right now that if I had to live as a citizen in the Soviet Union I couldn't have done it. I would have been locked up and thrown into Siberia very quickly because, if you are raised believing that you have a right to have an independent view and a government then comes along and says you have no such right, you go into rebellion or you could go into rebellion. For me - the idea of being ‘red or dead?’ - I'd end up on the dead side probably pretty quickly.