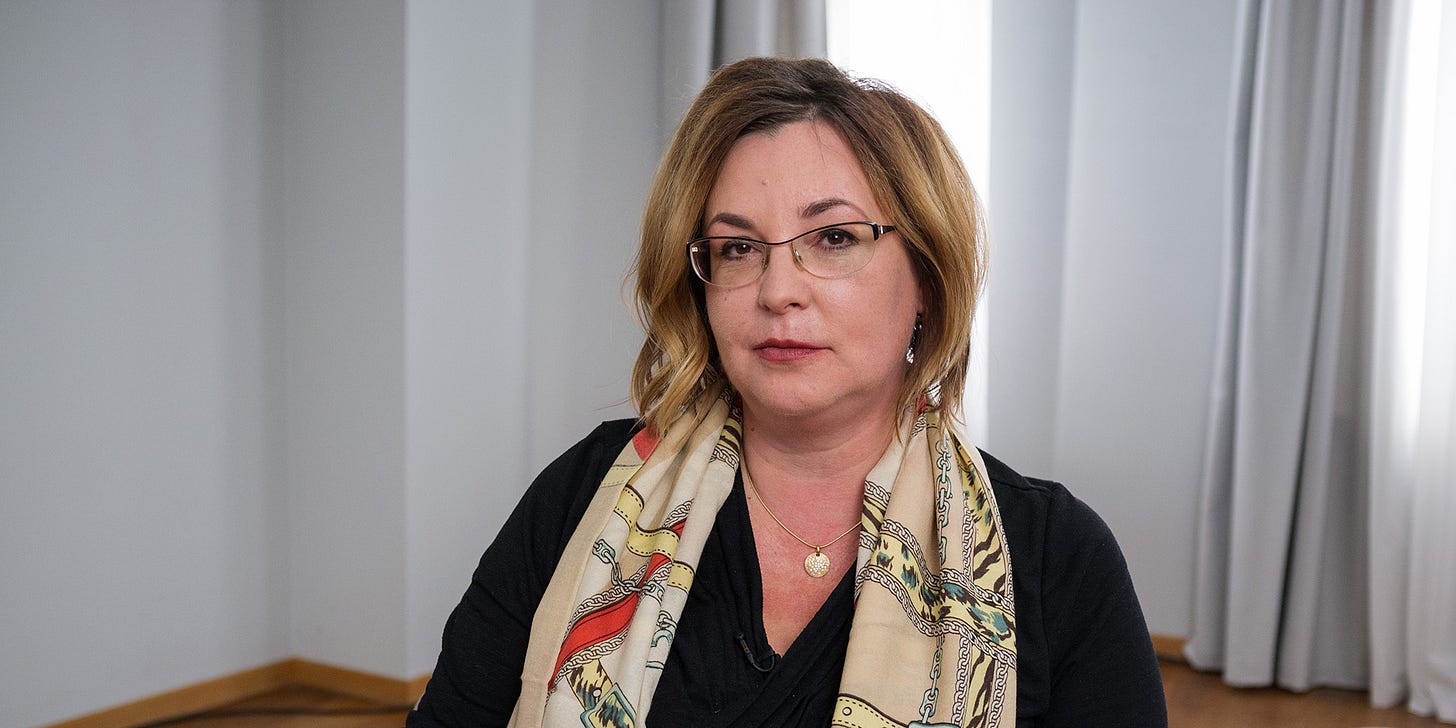

Интервью с политологом Ириной Буcыгиной об её книге 'Отношения России-ЕС и Oбщее Cоседство'

Interview with political scientist Irina Busygina about her paper 'Russia–EU Relations and the Common Neighborhood' - English translation below

Похоже что западная аудитория забыла про Украину. Тем временем, постсоветские страны, которые хорошо помнят как выглядит жизнь под правительством России, готовятся к возможности встречи с Российскими войсками у своих границах. На презентации Университета Колумбия о «Последних событиях на Украине» в Феврале, Украинский экономист Тимофей Милованов предупредил зрителей что, «Никто не верил, что Путин начнет полномасштабное вторжение в Украину, но он это сделал. Почему вы думаете, что он не сделает то же самое с такими странами, как Прибалтами и Грузией?».

Российский политолог Ирина Буcыгина называет этих стран «общим соседством». В 2017 году Бузыгина опубликовала свою книгу «Отношения Россия-ЕС и общее соседство», в которой она анализировала как Украина, Грузия, Беларусь и Турция деликатно балансируют между властью ЕС и Российским принуждением, и поэтому сталкиваются с постоянными проблемами безопасности.

Я брала интервью с Буcыгиной об ее исследованиях. В этом интервью она рассказывает о дискурсе про «распад Европы» и его влиянии на отношения России и ЕС, о реакции ЕС на войну в Украине, о том, чего ожидать для будущей безопасности государств общего соседства, и об освещение событий в России заподными журналистами.

Кажется, что сейчас, идея «распада Европы» набирает популярность одновременно с популярностью «ультраправых» в западе. Эта идея также является центральной в кампании Путина против запада. Считаете ли вы, что есть какая-то обоснованность в рассуждениях об этом так называемом «распаде»?

Я думаю что мы должны внимательно смотреть за теми словами которые мы употребляем, потому что слова это дискурс и довольно важно, какие слова мы используем. Реалисты всегда употребляют очень жестокие, сильные и преувеличенные слова. Например, слово «распад» который вы упоминали - «распад Европы». Если бы человек был бы не реалистом, как я скажем, он бы сказал так - «возможное ослабление структуры европейского союза». А говорить «распад Европы» это во первых агрессивный дискурс. Распад, у которого как будто нету обратного пути - это как бы конец, это всё. С моей точки зрения, это такой сугубый реализм - который специально играет со словами. Это с моей точки зрения довольно агрессивный дискурс, и он не научный потому что если мы все таки академики, то вообще то мы должны сказать что мы не знаем - вот это будет правильный ответ. Если человек выступает и говорит «я все знаю о будущем» то значит что он либо врет, или он дурак, или он реалист, или он специально пытается манипулировать своей аудитории.

Конечно мы понимаем, что ультраправые всегда были, всегда есть, и всегда будут, потому что Европа это демократия. Демократия это присутствие разных политических сил. Это же не Россия. В России, вы можете задушить любую политическую силу которая есть, которая альтернативная, и сказать «смотрите как у нас хорошо, у нас этого нет», а Европа живет в таких условиях что это побочный продукт Европейского (не только демократии) плюрализма. В Европе всегда будут такие группы. Именно это, как бы, плата за плюрализм.

Я занимаюсь Германией более пристально, у меня первый иностранный язык это немецкий, и если мы вспомним шестидесятые годы, вспоминается фракция красной армии. Это были террористы. Интеллигентные молодые люди которые были террористами, брали заложников. Тогда тоже все кричали что всё, наступает конец. Но, тем не мения, конец так и не наступил. По этому, это же не вопрос сказать распад Европы или конец Европы, а вопрос должен быть поставлен, как я думаю, так - «Как с этим жить?» Какие механизмы использовать чтобы вот этот дискурс, и чтобы эта политическая сила, не становились доминирующей. Чтобы не она определяла. Даже не о том чтобы её уничтожить, а о том чтобы она занимала бы свое место если, конечно, она находится в конституционных рамках. На пример, в Германие запришена Компартия, коммунистическая. Но партия АФД, которая тоже довольно радикальная, не запришена.

То что мне не нравиться про реалистов, это то что они пытаются сделать очень сложную реальность простой. Проще всего сказать «распад Европы». Нo я бы им сказала - а посмотрите какую удивительную стрессоустойчивость демонстрируют Европейский союз. В очень сложных условиях, он как раз не распался.

По поводу Украины, они приняли уже тринадцать пакетов санкций, на которые каждое государство должно было согласиться. Любое государство может блокировать санкции. Они сейчас готовят о четырнадцатом пакете санкций.

Это вопрос о том, что вы хотите увидеть. Если вы хотите увидеть распад, то он у вас в голове, и вы ищете для него причины. Вы ищете доказательство. Но полно другого доказательства противоположного, поэтому - возвращаемся к началу моего ответа - что Европейский союз это очень сложная реальность в которой есть все. Как академики, мы должны смотреть на разные тренды, а не торопиться объявлять «распад Европы», как делают реалисты.

Вы, в своей cтатьи, говорили о процедуре санкций и объясняли, как они являются слабыми. Считаете ли вы, что ЕС слишком сильно полагается на санкции и, следовательно, отстает в других областях противостояния российской власти?

Мой ответ это да. Мы должны думать что есть в распоряжение европейского союза, а что он может сделать. Мы должны посчитать как он устроен. Европейский союз это многоуровневая система в которой, именно в области внешней оборонной политики, очень много силы расположено между странам. Это не общий рынок. Вот есть общий рынок в нутряной политике Европейского союза и там действует так называемая ‘Key Communautaire’, это вот общие законы и общее институты. Но это именно внутренняя сфера Европейского союза. Как только Европейский союз выходит за свои границы то сразу начинаются покорители государств членов, не Европейского союза. У Европейского союза нет армии, у него нет оружия. Европейский союз это система правил. Рынок Европейского союза это рынок двадцати семи членов. У европейского союза в некотором смысле нет даже территории. Европейский союз это Брюссель, это режим правил который что-то может а что-то не может. По этому говорить о том что Европейский союз мог бы делать что-то что он не делает это не правильно потому что у него нет возможностей это делать, потому что так устроена эта система.

Для того, чтобы это было по другому, нужно проводить реформы внешней и оборонной политики. Эти реформы давно обсуждаются, но сделать их очень трудно потому что на них должны согласиться все страны. Страны очень не любят соглашаться на реформы именно в области внешней политики потому что это их суверенитет. У Европейского союза нет национального интереса. Он просто отсутствует. А у стран есть национальные интересы, и они хотели бы их сохранить.

Особенно трудно проводить реформу во время кризиса. Это вам скажет любая теория, потому что кризис раскалывает. Есть те страны которые проводят очень активную политику - помогают Украине оружием. Это Польша и Прибалты. Это Великобритания, которая больше не член Европейского союза, но вы понимаете. Это в некоторой степени Германия и так далее. Но есть страны которые не делают практически ничего, кроме гуманитарной помощи, которая совершенно другой вопрос. Сейчас, кроме санкций, которые согласовать тоже очень трудно, Европейский союз пытается формировать политику сопротивления российской компании дезинформации, потому что огромные деньги тратит Путин на дезинформацию стран Европейского союза. Европейский союз пытается коллективно с этим бороться.

Конечно только санкции действуют не так эффективно как бы хотели. Но никогда, ни в одном из случаев в мире применения санкций они не действовали так эффективно как бы хотели. Всегда, их эффективность слабая. Россия - страна такого размера, и в общем такого ресурсного богатства, что санкции не могут изменить ситуацию. Они могут изменить ситуацию в комбинации с другими факторами. Но сами по себе, санкции изменить ситуацию не могут. Европейский союз делает все что он может.

Что прогнозирует нынешняя ситуация в Украине для будущего других стран общего соседства, таких как Грузия и Беларусь?

Я себя всегда спрашиваю - я могу это исключить? Ответ - нет, не могу. Тогда я задаю себе следующий вопрос - а это вероятно? Я бы сказала что, сейчас - нет. Это не очень вероятно, потому что у России нет возможности сейчас воевать на несколько фронтов. Не потому, что у нее нет оружий. У России есть оружии потому что - и это очень страшно что там происходит - там полная милитаризация экономики. Они восстанавливают очень быстро на государственные деньги этот Военно-промышленный комплекс, и эти заводы работают двадцать четыре часа, семь дней в неделю - они делают оружия.

У России есть другая проблема. У нее слишком мало людей. Значит им нужна еще одна мобилизация. Россия уже провела одну мобилизацию в сентябре двадцать второго года. У них это называлась частичная мобилизация, но тем не менее мобилизация. Нужна еще одна мобилизация.

Так вот, до президентских выборов, мобилизации конечно не будет сейчас. Но после выборов, когда Путин опять победит, (это будет уже его пятый срок, пятый срок! Это уже уму непостижимо. Целое поколение выросло при нем, представляете себе?) вот тогда он может объявить мобилизацию. Но этому не имеет пока смысла. Ему нужно пока показать результат на Украине. Он не может пока показать какой то результат, но ему нужно показать, потому что это все делается для внутренней аудитории, что ‘мы можем, мы победители, мы освобождаем Украину от неонацизма’, весь их этот дискурс ужасный.

Ему нужно показать результат. Он не может сейчас начать, даже если он хочет, какие то действия против Прибалтики. Белоруссия это его союзник. Грузия это сложный вопрос, потому что там есть очень много Русской симпатии в политике. А вот, против Прибалтики - маленькие страны, бывшие республики советского союза, но это может случиться действительно. Не сейчас, а если будет катастрофа с Украиной, тогда да. Потому что, обратите внимание как говорил Путин когда он давал интервью Такеру Карлсону. Я смотрела это интервью. Что сказал Путин, когда тоже ему задали такой вопрос. Знаете как он ответил? Он сказал ‘А нам это сейчас не надо’. Вот, что он ответил. Он не сказал, что есть какие то международно признанные границы. Нет, он не сказал. Он сказал «я, Путин, сейчас этого не хочу». Но, ключевое слово это «сейчас». А через год, «Захочу. Или через два года захочу». То есть, он фактически открыто может это говорить.

Агрессия России против других стран может быть остановлена только объективными факторами. Если будет защита, если NATO даст твердый сигнал что будет тогда большая война, если у Европейский союза действительно будет большая реформа расходов на зарубежную оборону. Только это может остановить Путина, потому что он ментально, в голове, этому готов.

Есть ли у вас какие-то советы относительно подхода к репортажу о России с точки зрения западного журналиста?

У меня есть совет общего характера, из моего опыта общения с американскими журналистами. Это - больше читайте и старайтесь говорить с разными людьми.

Россия такая страна что в ней всегда что то можно найти - всегда. Если вы хотите найти протесты, вы найдете протесты. Хотите екологические? Найдете екологические. Хотите социальные? Найдете социальные. Там очень большая территория и очень много разного. Но, журналисты почему то не отличают как бы случаев от тенденций.

Когда вы говорите с кем-то, берете интервью, то хорошо когда вы спрашиваете «объясните мне пожалуйста…». Вот это правельный, по моему, вопрос. А когда журналисты говорят «подтвердите мне…», неслиянность считаю что что-то н правилно то я не хочу это подтвердить. Если вы хотите изучать глубоко, и какие то делать именно новые ваши репортажи или то что вы пишите, то мне кажется, конечно нужно придумать какой-то свежий аргумент. Но этот свежий аргумент нужно уметь объяснить. Это не должна быть просто какая-та конструкция которая вот у вас в голове. Это должно быть все объяснено.

Американские журналисты, так же как и Немецкие, кстати, с которыми я тоже очень много имела дела, ко мне приходят уже со своим знанием. Им не нужны мои объяснения, им нужны мои подтверждения. И этого вот я не хочу, и потом они пишут статьи которые тебе ничего не дают. Я все равно всегда стараюсь что-то объяснять, но нужно, по моему, писать такие статьи, чтобы они запоминались. Не то, что написать тысячу статей, или сто статей, а то чтобы каждая статья чем то запомнилась. Чтобы это было ваше имя. Чтобы каждый материал чем то запомнили, и запомнили тем самым ваше имя.

Фактически, Россия им не интересна. Вот они спрашивают меня про Россию, ну я вижу что она им не интересна. Хорошо, пусть она им будет не интересна, но они берут у меня интервью и пусть хотя бы послушают меня.

Спасибо Ирине Бузыгиной, что отделила время чтобы поговорить со мной о своей работе.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION BELOW

Western audiences seem to have turned a blind eye on Ukraine. Meanwhile, post-Soviet states - that remember all too well what life looks like under Russian occupation - prepare for the possibility of meeting Russian forces at their borders. At a Columbia University presentation on ‘The latest from Ukraine’ in February, Ukrainian economist Tymofiy Mylovanov warned that “No one believed that Putin would launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but he did. What makes you think he won’t do the same to countries like the Baltics and Georgia, for example?”.

Russian political scientist Irina Busygina refers to these countries as the ‘common neighborhood’. In 2017, Busygina published her paper Russia–EU Relations and the Common Neighborhood, which analyzes how Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, and Turkey are balanced delicately in the tug of war between EU authority and Russian coercion, therefore facing constant security issues.

I spoke to Busygina about her research. This interview covers her thoughts on the discourse of the “collapse of Europe” and its impact on Russia–EU relations, the EU’s response to the invasion of Ukraine, what to expect for the future safety of states in the common neighborhood, and Russian news coverage by western journalists.

It seems that recent discourse over the “collapse of Europe” is gaining popularity simultaneously with the rise of the far-right in the West. The idea is also central to Putin’s campaign against the West. Do you feel that there is any validity to the prediction of this so-called collapse?

I think that we should be mindful of the words that we use, because words create discourse. Realists always use very cruel, strong and exaggerated words. For example, the word “collapse” that you mentioned - “the collapse of Europe”. If a person were not a realist, for example myself, they would refer to the situation as “a possible weakening of the structure of the European Union”. To say “the collapse of Europe” is, first of all, an aggressive discourse. A collapse that seems to have no way back implies the end, definitively. From my point of view, this deliberate play on words is a prime example of realism. This, from my point of view, is a rather aggressive discourse, and it is not scientific because, if we are academics, then in general we must say that we do not know - this would be the correct answer. If a person speaks out and says “I can predict the future”, it means that he is either lying, he is a fool, he is a realist, or he is deliberately trying to manipulate his audience.

Of course we understand that the far-right has always been, always is, and will always be, because Europe is a democracy. Democracy is the presence of different political forces. This is not the case in Russia. In Russia, you can strangle any political force that exists as an alternative, and say “look how good we have it, we don’t have those problems” but Europe lives in such conditions that this is a by-product of European (not only democracy) pluralism. There will always be groups like this in Europe. This is, you could say, the price to pay for pluralism.

I study Germany more closely - my first foreign language is German - and if we remember the sixties, we remember the Red Army Faction. These were terrorists. Intelligent young people who were terrorists, who took hostages. Then, too, everyone shouted that everything was coming to an end. But, nevertheless, the end never came. Therefore, it is not a question of the collapse of Europe or the end of Europe, but the question should be posed, I think, this way - “How do we cope with this?”. What mechanisms should be used so that this discourse, and this political force, does not become dominant, so that it does not determine? The goal is not to destroy it, but to ensure that it takes its place if, of course, it is within the constitutional framework. For example, the Communist Party was banned in Germany. But the AFD party, which is also quite radical, was not banned.

What I don't like about realists is that they try to frame a very complex reality as a simple one. It is too easy to say the “collapse of Europe”. I would tell them - look at the amazing resistance to stress that the European Union demonstrates. In very difficult conditions, it has not collapsed.

Regarding Ukraine, the European Union has already adopted thirteen packages of sanctions, to which each state had to agree. Any country within the union can block sanctions. They are now preparing the fourteenth package of sanctions.

It's a question of what you want to see. If you want to see collapse, then it is in your head and you are looking for reasons for it. You are looking for proof. But there is plenty of other evidence to the contrary, therefore - back to the beginning of my answer - the European Union is a very complex reality in which everything is present. As academics, we should look at different trends and not rush to declare the “collapse of Europe”, as realists do.

In your paper, you discussed sanctions and explained how ineffective they are when functioning on their own. Do you think the EU is relying too heavily on sanctions and is therefore falling behind in other areas when confronting Russian power?

My answer is yes. We must consider what the European Union has at its disposal and what it can do. We must consider how it works. The European Union is a multi-level system in which, specifically in the field of foreign defense policy, a lot of power is distributed between member states. There is no common market. There is a common market in the internal politics of the European Union and there is a so-called ‘key Communautaire’ in this regard; there are common laws and common institutions. But this is limited to the internal sphere of the European Union. As soon as we look at the EU’s sphere of foreign policy, the autonomy of member states, not the European Union itself, increases. The European Union has no army, it has no weapons. The European Union is a system of rules. The European Union market is a market of twenty-seven members. The European Union, in a sense, does not even have territory. The European Union is Brussels; it is a regime of rules that can do some things and cannot do others. Therefore, to say that the European Union should do something that it has not done is not correct because that would be outside the realm of its possibility, because of the way that it is structured.

In order to change this, it is necessary to carry out reforms in foreign and defense policy. These reforms have been discussed for a long time, but they are very difficult to implement because all countries must agree to them. Countries are hesitant to agree on reforms specifically in the field of foreign policy because they value their sovereignty. The European Union has no national interest. That is simply missing. Countries themselves have national interests, and they would like to preserve them.

Reform is especially difficult during a crisis. Any theory will tell you this, because a crisis inherently divides. There are countries that pursue a very active foreign defense policy - they provide Ukraine with weapons. These countries are Poland and the Baltic states. This is also the UK, which is no longer a member of the European Union, but nevertheless. This is to some extent Germany and so on. But there are countries that do practically nothing except provide humanitarian assistance, which is a completely different issue. At the moment, in addition to sanctions, which are also very difficult to agree on, the European Union is trying to formulate a policy of resistance to the Russian disinformation initiative, because Putin spends a lot of money on disinformation targeted at the countries of the European Union. The European Union is trying to collectively fight this.

Of course, sanctions are not working as effectively as they would like. But never, in any case in the history of sanctions, have they acted as effectively as they would have liked. Their effectiveness is always lacking. Russia is a country of such size, and in general such wealth of resources, that sanctions cannot make a significant impact. They can change the situation in combination with other factors, but sanctions themselves cannot change the situation. The European Union is doing everything that it can.

What does the current situation in Ukraine predict for the future of other countries in the common neighborhood, such as Georgia and Belarus? Should we expect that Putin will take actions against them as well?

I always ask myself - can I rule this out? The answer is no, I can't. Then I ask myself the following question - is this probable? I would say that at the moment - no. This is not very likely, because Russia does not currently have the ability to fight on several fronts - not because it doesn't have weapons. Russia has weapons because - and this is a very scary thing that is happening there - there is complete militarization of the economy. They are very quickly rebuilding their Military Industrial Complex with government money. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, these factories are making weapons.

Russia has another problem. They are lacking in terms of infantry. This means they need another mobilization. Russia has already carried out one mobilization in September of 2022. They called it partial mobilization, but mobilization nonetheless. Another mobilization is needed.

But, of course, there will be no mobilization now until the presidential elections. But after the elections, when Putin wins again (this will be his fifth term, fifth term! This is incomprehensible. An entire generation grew up under him, can you imagine?) then he can announce mobilization. But it doesn’t make sense to do so yet. He needs to show results in Ukraine for now. He cannot show any results yet, but they need to be shown, because this is all being done for the internal audience, to show that “we can do this, we are winners, we are liberating Ukraine from neo-Nazism”, their whole terrible discourse.

Putin needs to show results. He cannot start now, even if he wants, some kind of action against the Baltic states. Belarus is his ally. Georgia is a difficult issue because there is a lot of Russian sympathy in politics there. But the Baltic states are small countries, former republics of the Soviet Union, so this can really happen. Not now, but if the invasion of Ukraine ends catastrophically, then yes. I predict this because of what Putin said when he gave an interview to Tucker Carlson. I watched this interview. What did Putin say when he was also asked this question? Do you know how he answered? He said, “We don’t need this now”. This is what he replied. He did not say “There are internationally recognized borders”. No, he didn't say that. He said “I, Putin, don’t want this now”. But the key word is “now”. A year later, it may turn into “I want to”. Or in two years. He can actually say this openly.

Russia's aggression against other countries can only be stopped by objective factors. If there is defense, if NATO gives a firm signal that there will then be a big war, and if the European Union really carries out a large reform to its foreign defense spending. Only this can stop Putin, because mentally, in his head, he is ready to invade.

Do you have any advice on how to approach reporting on Russia as a Western journalist?

I have some general advice gathered from my experience with American journalists. That is - read more and try to talk to different people.

Russia is such a country that you can always find something within it - always. If you want to find protests, you will find protests. Do you want to find environmental protests? You will find environmental ones. Want social protests? You will find social ones. There is a very large area and a lot of different issues to be found. But for some reason journalists do not distinguish cases from trends. They see the country in black and white, In fact, they are not interested in Russia. So when they ask me about Russia, well, I see that they are not interested in it. But even if they are not interested in it, they are still interviewing me and so at least they should listen to my answers.

When you are talking to someone, interviewing someone, it is good to ask “please explain to me...”. That is the right question, in my opinion. When journalists say “confirm for me...”, I often don’t think that what they are asking me to confirm is right so I don’t want to confirm it. If you want to study a subject deeply and conduct meaningful reporting, then it seems to me that you need to come up with some kind of fresh argument. But this fresh argument needs to be explained. It shouldn’t just be some line of reasoning that you’ve made up in your head. It should be explainable.

American journalists, as well as German ones, by the way, with whom I have also dealt with often, come to me with their own preconceived ideas. They don't need my explanations, they need my confirmations. This is what I don’t want, and then they write articles that lack substance. I still always try to explain something, but, in my opinion, you need to write articles so that they are remembered. The goal isn’t to write a thousand articles, or a hundred articles, but to make each article memorable in some way. Remember that you are writing under your name. Aim to have each article be remembered in some way, so therefore your name is remembered.

Thank you to Irina Busygina for taking the time to speak to me about her work.